Korea Archery recently published videos of “Special Matches” between national team members at the country’s national training center. The videos had an unusual feature that I haven’t seen before: the competitors’ heart rates.

The feature only appeared a few times per match, and usually only covered a few seconds so often one archer was shooting while the other archer was just standing still between shots.

The heart rate values themselves jumped around significantly and the software had some difficulties in recognising moving faces. So there’s a fair amount of scatter and it’s not clear whether the numbers captured at that point are representative of each athlete’s heart rate over the rest of the match, or whether the heart rate overlay was taken at the same time during each match.

Previous uses

The technology used is fairly new and is mostly the topic of research papers, not a mature technology. There are two methods I’ve read about to get heart rate from videos: looking at the subtle change in skin colour with the oxygenation of the blood, or looking at small movements to the head caused by the heartbeat. There’s an interesting review of the techniques used here.

Heart rate and elite archery

I remember my archery coach telling me many years ago that scientists had found that Olympic archer’s best shots happened when they released the string between heartbeats, and therefore a low heart rate was important to decrease the chance of the release happening during the heartbeat. This made intuitive sense to my teenage self since the heart beat can be felt with a finger, which means motion, which would add variability to an archer’s release or the direction they’re pointing the bow.

I found the study in 1989 that must be the one my coach heard about, and read through it. The study participants were four elite Australian archers: one compound archer, one 17 year old male recurve archer, one 21 year old female recurve archer, and one 51 year old female recurve archer – quite the sample size! Hopefully they and their hearts are representative of elite archers in general. Each archer shot a series of arrows on several different days while their heart, balance, and timing were monitored by the researchers. The metric used to classify arrows is in the table below.

Most of the arrows shot were considered “good”. The average heart rate of the three recurve archers during the “good” arrows was 90 BPM just before the release, while it was 96 BPM at the same point in the cycle during the “average” and “bad” shots. The difference isn’t large but it was consistent between the three archers. The resting heart rates were 6-25 BPM lower than the values when they were shooting.

Does this mean that the archers were more accurate when their heart rate was lower? Not necessarily, because the measure of a “good” arrow was subjective. If a shot hit the middle but either the archer or coach didn’t think the shot felt or looked quite right, it was considered “average” instead.

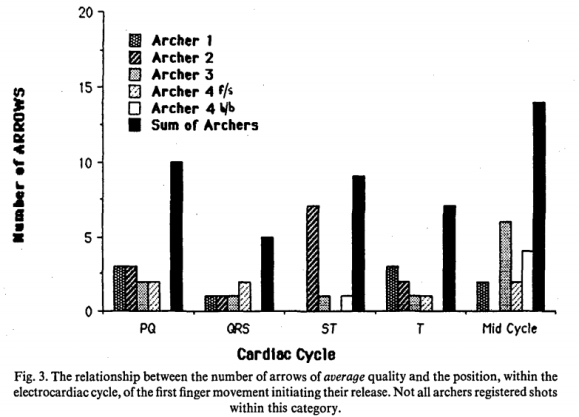

The study also looked at where in the cardiac cycle good, average, and bad arrows were released. The cardiac cycle is divided into several regions seen on an ECG. I was unfamiliar with the terminology, but found this site useful. In this paper, the regions used were PQ, QRS, ST, T, and the mid-region. The lengths of the different regions aren’t the same, and vary between people and with heart rate, so it’s not expected that a similar number of shots would happen during each part of the cycle in a random scenario. The study didn’t indicate the length of each part of the cycle for these archers. In practice, the PQ interfal lasts about 120-200 ms, the QRS part 80-120 ms, the Q-T interval 350-430 ms, and the mid-region time takes up most of the remainder. When the heart rate increases, the Q-T interval decreases a little, but most of the decrease in cycle time happens during the rest of the cycle, according to here and here. If a heart beating sounds like “ba-dum, ba-dum, ba-dum”, then the QRS part is the “ba” and the T region is the “dum”, so the ST portion is in between the “ba” and “dum” and the mid-region and PQ region together make up the time from the end of one beat to the beginning of the next.

Looking at how many “good”, “average”, and “bad” shots happened during each phase of the cycle, it’s clear that the distribution is different between the good shots and the average or bad shots. It looks like good shots happened disproportionately more during the ST and mid-cycle portions – much more so than could be reasonably explained by those sections being maybe up to 40 ms longer during the good shots.

Comparing the ratio of good to average or bad shots within one part of the cardiac cycle is a more quantitative method as it doesn’t depend on knowing the relative duration of each part of the cycle. As the heart rate only changed by about 6 BPM (35 ms) between the two types of shot, the duration of each part of the cardiac cycle shouldn’t have changed significantly.

| PQ | QRS | ST | T | mid-region | |

| ratio of good:other shots | 1.2 | 0.7 | 3.8 | 0 | 2.8 |

Based on these ratios, it looks like arrows released during the ST phase and mid-region were much more likely to be good shots. Does this mean that archers were more accurate then? Not necessarily, since shots released during the other phases that were just as accurate but didn’t feel “good” to the archer would have been classified as “average”. It may be that shots released during the QRS and T region, when the beat of the heart is felt, feel worse but are not less accurate.

Regardless of how long each part of the cardiac cycle was for each archer, there is a clear difference in the fraction of arrows shot during each part of the cycle. The archers would have been using a clicker to provide an audible indication of when the arrow was drawn back to a set distance. The time between the sound of the clicker is similar to the auditory reflex time. This time was not measured in the study, but it would have been interesting to know whether the time between the click and the release was more variable during the good shots in order to line up better with the ST or mid-region of the cardiac cycle, or whether it did not vary more than usual. The latter would indicate some synchronisation between the archer’s cycle of drawing the bow, aiming, and releasing, and their heart rate.

Heart rate variation and accuracy for elite archers

A 2020 article here followed a similar methodology. 4 compound and 3 recurve elite male Indian archers were filmed shooting while wearing a heart rate monitor. The study found that for all archers, the average heart rate decreased during the 5 seconds before the arrow was released, and continued to decrease until 3 seconds after the shot, after which it rose again. The mean heart rate when archers shot an 8 was about 8 BPM higher than when they shot a 9 or 10, which was statistically significant. While the mean heart rate was 1 BPM higher for shots that scored a 9 instead of a 10, this difference was not statistically significant.

In contrast, a 2015 article here showed the opposite relationship between heart rate and score in 3 female and 1 male recurve archer. The heart rate was about 10 BPM higher during shots that scored a 10 than those that scored 8.

Heart rate monitoring and accuracy

Another paper looked at the both effect on accuracy of both the time in the cardiac cycle when the arrow released, and of hearing the archer’s heart beat. 36 people aged 16-24 participated. I couldn’t tell whether the archers were elite, experienced, or novices due to the paper being in Japanese and using Google Translate. The shooting distance was 50 m, but the target face wasn’t specified. The average arrow value was 7, which would be too low for elite archers on a 80 cm target face, but also too high for beginner archers on a 122 cm face. Each archer shot 6 arrows under normal conditions, and 6 with a earpiece playing back the sound of their heart.

Without the heartrate feedback, 53% of shots were released during ventricular systole (the “ba-dum” sound), while this was only 36% when wearing the earpiece. The scores are in the table below:

| no earpiece | with heartrate played back | |||||

| score | std. dev | shots | score | std. dev. | shots | |

| systole | 6.8 | 2.3 | 114 | 6.9 | 2.3 | 77 |

| diastole | 7.3 | 1.9 | 102 | 7.6 | 1.8 | 139 |

The difference in average score for shots during each part of the cardiac cycle did not show a stastitically significant difference when the heartrate playback was added. However, the fraction of shots that were released during diastole increased and therefore so did the average score of the archers when they could hear their pulse. The heart rates did not change significantly when the earpiece was added, so the relative duration of systole and diastole should not have changed either.

It would be interesting to know whether this effect would persist if more than 6 arrows per archer were shot, and whether archers who were accustomed to that feedback shot better or worse in competitions where electronic devices aren’t allowed.

Heart rate for experienced and inexperienced archers

This study from 2011 compared the heart rate and score of experienced and inexperienced archers. The experienced archers shot higher scores and had lower heart rates. The heart rate was only measured during shooting, so there’s no way of knowing whether the resting heart rates of both groups were the same and the inexperienced archers had a larger increase in heart rate during shooting, or whether the experienced archers already had a lower heart rate due to long term physical activity and both groups had the same increase in rate when shooting. The study concludes experience in archery results in both better accuracy and lower heart rate, but that is not necessarily supported by their data. Had the researchers also told the subjects to, for example, run for several minutes before shooting so as to elevate their heart rate, then they would have been able to see whether experience alone was enough to give their result, or if heart rate also played a role.

Results

I was curious as to whether the heart rate overlay was just a silly novelty or if it had any relation to the match. All these archers are world class and would be expected therefore to have good control of their nerves during matches. As there were 7 matches between the female archers and 8 between the male archers, I tabulated what looked like a representative heart rate for each archer based on the values on the screen. For videos where there were multiple instances of the heart rate replay I used the first one, which was after the first or second end. After writing down the heart rates, I checked who won the match.

| Target 1 | Target 2 | Target 1 HR | Target 2 HR | Winner | Winner lower heart rate? |

| Yoo Su Jung | Chang Hye Jin | 82 | 66 | 2 (SO) | yes |

| An San | Chang Hye Jin | 62 | 69 | 1 | yes |

| Yoo Su Jung | Lim Si Hyun | 75 | 80 | 1 (SO) | yes |

| Yoo Su Jung | Kang Chae Young | 72 | 54 | 2 | yes |

| Lee Ga Young | Chang Hye Jin | 72 | 63 | 2 | yes |

| An San | Kang Chae Young | 56 | 60 | 1 | yes |

| Jeon Ina | Kang Chae Young | 90 | 65 | 2 | yes |

| Target 1 | Target 2 | Target 1 HR | Target 2 HR | Winner | Winner lower heart rate? |

| Kim Woo Jin | Lee Woo Seok | 65 | 54 | 1 | no |

| Bae Jae Hyun | Kim Je Deok | 95 | 70 | 2 (SO) | yes |

| Kim Woo Jin | Bae Jae Hyun | 66 | 62 | 1 | no |

| Lee Woo Seok | Kim Je Deok | 75 | 85 | 1 | yes |

| Oh Jin Hyek | Lee Woo Seok | 92 | 81 | 2(SO) | yes |

| Kim Woo Jin | Lee Seung Yoon | 66 | 55 | 1 | no |

| Bae Jae Hyun | Han Woo Tak | 77 | 86 | 1 | yes |

| Kim Jong Ho | Kim Je Deok | 84 | 64 | 2 | yes |

Analysis

Heart rate difference between groups

Firstly, the heart rates are all over the place, going from 54 to 95 BPM. While this is a wide range, it’s still within the range of resting heart rates seen for the general population. The athletes aren’t at rest, but athletes tend to have lower resting heart rates for the general population, and doing a standing strength-related high stakes activity is expected to raise the heart rate, so maybe the two factors mostly cancel out.

The average rate from all the women’s matches was 68.8 BPM while that for the men’s matches was 73.6 BPM. For the same level of fitness, women tend to have a slightly higher heart rate than men by about 4 BPM so this is a bit of a surprise. A wide range of factors affect the resting heart rate though:

- exercise (lower in people who do more)

- body mass index (higher if higher)

- amount of sleep (too little or too much sleep give a higher rate)

- alcohol consumption the day before

- age

- time in the menstrual cycle

- some medications

- stress

- genetics

The heart rate during the match is some combination of the resting heart rate + whatever increase the athlete gets from standing up, using their bow, feeling the pressure.

So it could be that the female team, whose members are slimmer on average than the male team, always has a lower heart rate. Or maybe the male team normally has a lower heart rate, but they all had a late night and a few drinks the day before the matches – who knows.

Heart rate correlation with match result

In 12 out of 15 matches (80%), the winner was the athlete who had the lower heart rate at the time it was measured. If there was no correlation whatsoever, then we’d expect the athlete with the lower heart rate to win 50% of the matches, but there would still be about a 1.8% chance of the athlete with the lower heart rate winning at least 80% of the matches just by random chance – so quite unlikely but still possible.

However, it gets more interesting if we look at the 3 matches that were won by the athlete with the higher heart rate: they were all won by Kim Woo Jin. So 100% of the matches that didn’t include him had the athlete with the higher heart rate win – a probability of 0.02%.

While the correlation between heart rate and match result for archers who aren’t Kim Woo Jin is pretty clear, it says nothing about causation. If one causes the other, it could be either way around:

- The archer who has a bad start to the match (not necessarily a low first end score, but if they don’t feel quite right about their form in the first end) becomes more nervous and this causes their heart rate to go up.

- The archer with the lower heart rate is probably feeling calmer and is more likely to shoot their best.

This could also be cyclical, where perception of not doing well during the match increases the heart rate which reduces shot quality which increases the perception of not doing well etc.

I was quite surprised by this result because heart rate is varies a lot between people: one archer’s resting heart rate might be higher than another one’s “feeling anxious while shooting” heart rate. While I would expect an archer to shoot better when their heart rate is closer to their resting value as it probably means they’re calmer and better able to control fine movements, it seems odd that heart rate during the match, as opposed to the increase in heart rate relative to the archer’s resting heart rate value, was so closely associated with winning.

Later ends

I hadn’t noticed the first time I looked at the matches that most videos show several “BPM rewind”. I admit I was jumping forward during the videos to see if there were any interesting slow motion replays and the first match I looked at only had one heart rate clip. So to check how repeatable the previous correlation was, I looked at the other ends in the women’s matches that had heart rate data. Most of the ends that didn’t have heart rate data had a high speed video of one of the archers filmed at a frame rate between 200 and 300 fps.

Women finals

Gold final: after ends 1, 2, 4: An lower than Chang in all three videos.

Bronze final: after ends 2, 3: Yoo higher than Kang in both videos.

Women semi-finals

- Yoo vs Chang after 2, 3, 5: Yoo still about 15 BPM higher than Chang in 3rd end, but in the 5th end Chang instead was 15 BPM higher than Yoo.

- An vs Kang after 1, 3: An lower than Kang in both ends

Women quarter-finals

- Jeon vs Kang after end 2 only.

- Yoo vs Lim after end 1, 3: in the third end the reading cut out and both archers varied a lot over the same range.

- Lee vs Chang after ends 1, 3: the overlay in the third end has values that fluctuate by 15 BPM for both archers over a duration of a few seconds, which sounds like the program was struggling to read their faces.

So it looks like the heart rate difference between the two archers doesn’t generally change during the match either.

Conclusions

Neither the study of Australian archers, nor the videos of Korean archers are enough to say if there is a causative link between lower heart rate and better shots. There are many questions raised that would be interesting to know more about at a later date:

- Do elite archers shoot less accurately when their heart rate is elevated due to an external factor (like recent exercise)?

- Is it the heart rate during shooting, or the difference between the resting heart rate and the heart rate during shooting that is relevant here?

- Are elite archers more accurate when the arrow is released during the ST region and mid-region of the cardiac cycle? Is the same true for experienced and inexperienced archers?

- Is there any causation between increased heart rate and bad shots? If so, which way around is it?